Exercises Are Torches

Remember that moment when a math concept finally clicked? Chances are, it happened right after you solved a good exercise.

There is a reason for that.

In today’s world, students’ attention spans have been deeply affected—particularly after the pandemic. There are many possible causes: constant digital distractions, reduced social learning environments, increased academic pressure, or simply a change in how young minds interact with information. Regardless of the reason, it’s clear that long, abstract explanations no longer resonate with the majority of students.

And yet, some level of instruction is always necessary. Teachers must introduce new content, define concepts, and explain core ideas. Stronger academic students tend to thrive under this model—they’re more comfortable with abstract thought, they have robust mental frameworks, and they feel confident as they absorb information in large chunks.

But most students don’t operate that way. Many struggle to keep up, not because they’re incapable, but because their background knowledge is weaker, their confidence is fragile, and they need time to make sense of what’s being said. As a teacher (and a former student of this kind myself), I’ve seen this firsthand.

The solution? Deliver just enough instruction—no more than is strictly necessary to preserve scientific accuracy and range. Give students actionable knowledge. Concepts must be introduced clearly and concisely, with enough foundation to be meaningful, but not so much as to overwhelm. Then, allow the real learning to happen through exercises.

And here’s where the torch analogy comes in.

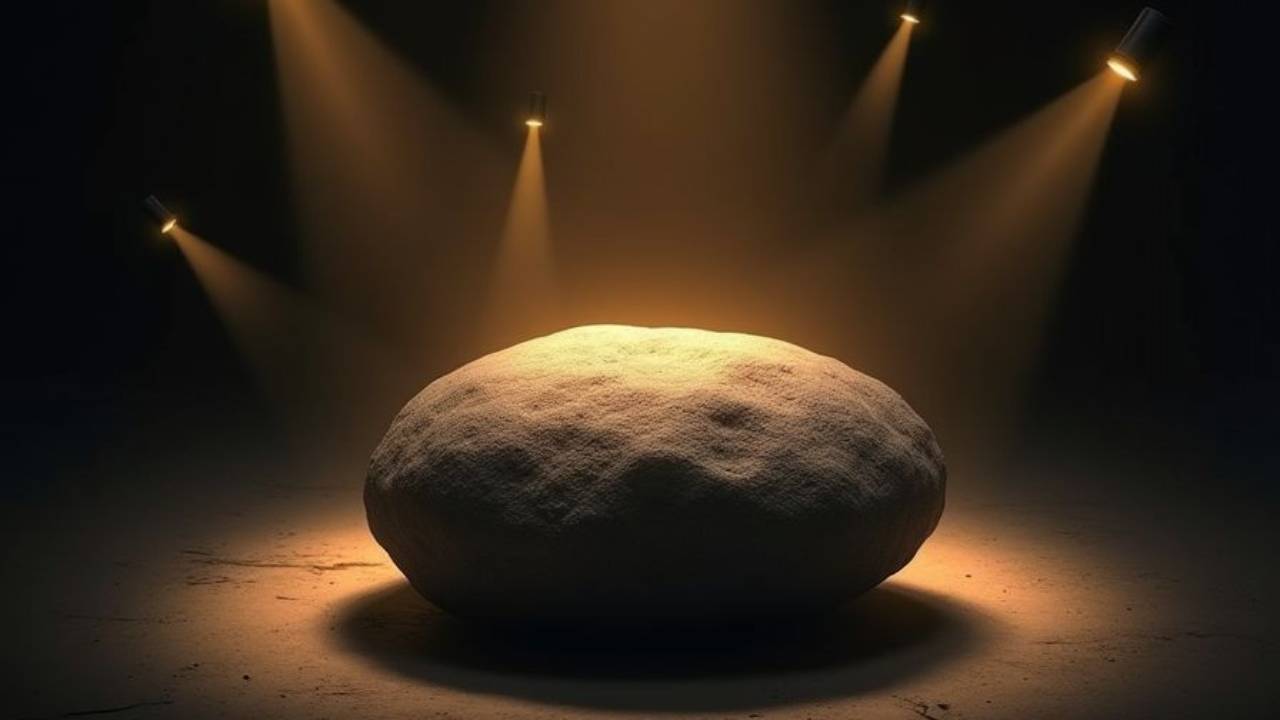

When I introduce a new concept in class, I tell my students to imagine that we’ve just placed an unfamiliar object in the middle of a dark room. Through instruction, I’ve described its outline, its location, and its approximate dimensions. They are aware of it—but it’s still mostly in the dark.

Now comes the important part: understanding that object fully. For that, we need light. Each exercise is a torch. Some are held close to the object, revealing a small detail with precision. Others illuminate it from a distance, helping us see how it fits into the bigger picture. Some beam from odd angles, uncovering unexpected features we hadn’t thought to look for. And only after a number of these torches have lit up the room from different perspectives do we begin to truly understand the object.

In mathematics, these torches are carefully designed exercises. They allow students to approach the same concept in multiple ways—logically, visually, algebraically, graphically, and sometimes even creatively. Each approach strengthens their internal model of the concept. Each exercise makes the room a bit brighter.

This principle is embedded in my learning methodology: the GHOST BUST Framework, a structure built specifically for educational systems that rely on high-stakes final exams, like CAIE IGCSE and A-Level assessments.

The first phase, Grab, is where students are introduced to the concept. This is the part where the object is placed in the dark room. The explanation is kept purposeful and actionable, helping students latch onto an idea quickly.

The second phase, Hold, is where the torches come in. This is the heart of active learning. The Hold phase is divided into three levels:

-

Test questions: simple and direct, ensuring the student has grasped the basic idea.

-

Play questions: creatively explore variations and applications of the concept.

-

Master questions: bring in real depth, challenging the student to see the object as a whole and in relation to other topics.

With this structure, students don’t just memorize—they see. They don’t just repeat—they understand.

And all of it starts with a torch. Or two. Or ten.

Because in the end, real understanding doesn’t come from staring into the darkness. It comes from shining light—again and again—until the concept is no longer hidden, but clear and complete.